Lees het artikel in het Nederlands!

Tineke Steenbrink’s search for the Stabat Mater of Pergolesi takes her on a journey of discovery

Tineke Steenbrink is a harpsichordist, organist, musicologist, and co-founder of the Holland Baroque Society, along with her twin sister Judith. Through her work as a teacher and her musical investigations for the Holland Baroque, Steenbrink aims to get as close as possible to the origins of each musical piece she encounters. In 2010, while working on Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater, she asked herself: Why is this work consistently described as a new style? Steenbrink shares her thoughts on Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater:

…After all, what could be more Baroque than the opening dissonances combined with the running bass? Corelli could have put his signature on it. Of course, I see new elements in this work. Small passages that could have been written by Haydn or Mozart. While reading the score, numerous questions arose in my mind: Are the indications I find (Sotto voce, Dolce assai, Andante amoroso) original? And what about the slurs over the whole measure at the beginning of O quam tristis et afflicta? This would contradict a number of Baroque rules. The last measures of the Amen at the end of the Stabat Mater struck me as rather abrupt. It’s as if the Amen crashes into the buffers like a train…

Questions

There are more questions, and Steenbrink embarks on a search for the only authentic manuscript of Pergolesi himself. Her quest begins with www.imslp.com, the International Music Score Library Project, an online library providing access to an extensive collection of sheet music and scores in the public domain, serving as a valuable resource for musicologists and musicians. Here, she discovers interesting manuscripts of the Stabat Mater from music libraries in Naples and Copenhagen, as well as a solo violin arrangement of the Amen by Johan Helmich Roman (1694-1758). Additionally, she finds printed scores and keyboard reductions from 1760 to 1858. In the last four measures of the Amen, the note values are noted as twice as slow as in the modern score. Does she have a correct edition? Unfortunately, www.imslp.org does not mention an autograph (the author’s own manuscript) of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater.

Montecassino

However, the autograph does exist! It is located in the Abbazia of Montecassino, a monastery between Rome and Naples. During the Battle of Montecassino on February 15, 1944, the monastery was bombed by the Allies. They believed that German soldiers were taking cover there. The monks anticipated this and safeguarded the library and other art treasures. However, everywhere she reads, Steenbrink finds that access to the original manuscript at Montecassino is denied. But Steenbrink doesn’t give up:

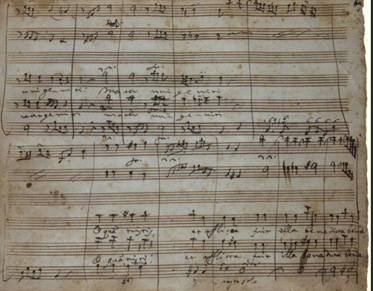

Claudia Lotti, who works in our office (of Holland Baroque) and is half Italian, calls the monastery on my behalf and requests a copy of the autograph. It has not yet been digitized or put on microfilm, so the monastery arranges for a photographer from the village to take pictures of every page. Then, I hear nothing for a while. Finally, on August 17, 2010, the photographer shows up. Suddenly, I am in possession of 38 photos of the Stabat Mater. Unbelievable! I am moved by the beauty, all the little notes in the margins, the adjustments. It is clearly visible how the work flowed from his pen. And then, on the last page: a correction has been made in the Amen, the final measures have been slowed down to half the tempo. The ink is faint, lighter than the rest. There is no indication of who made this correction and when.

The myth tells that Pergolesi completed this work on his deathbed. Does this mean that he couldn’t make the corrections? Or does the faint ink prove the truth of the deathbed myth? Who made this correction to the final measures and when? …

Facsimile edition

The news that Steenbrink possesses photos of the autograph spreads in the world of music. A German publisher proposes creating a facsimile edition of the manuscript. Why not? But will the monks grant permission for that? Italian diplomacy through a friendly abbot proves effective.

…I present the whole story to Andrea Marcon, an Italian organist, harpsichordist, and conductor specializing in Italian Baroque music. He believes that the correction was made shortly after Pergolesi’s death by a musician who still thinks and feels in the Baroque style and perceives the ending as too abrupt. This makes me think: I am also a ‘Baroque’ musician, did I feel annoyed by the final measures in the same way, and am I reacting as conservatively as the reception of Pergolesi’s new style right after his death? I doubt the indications in the score that seem too late to me in terms of style. Am I old-fashioned, and is Pergolesi way ahead of me? Does this also answer the question of why this piece made such an impact and represents a new style? …

Jos Biemans, a manuscript expert from the Special Collections department of the University of Amsterdam, cannot determine with 100% certainty if the corrections to the final measures are by a different hand than Pergolesi’s. According to him, they seem to point towards Pergolesi himself, but he doesn’t provide a definite answer.

In 2011, Steenbrink examines numerous scores and parts. It turns out that there is a good, correct score, but there are only terribly bad parts available: the publishers cram the instrumental material full of instructions.

Providing a facsimile edition and good instrumental material is seen by Steenbrink as her task. This edition has been realized.

Results of Steenbrinks research

Steenbrink found subtle deviations in dynamics, phrasing, and ornamentation in the original manuscript compared to contemporary performances of the Stabat Mater. She discovered indications for expressive embellishments that are often overlooked in modern interpretations. She also found notations that were common in the Baroque period but had been forgotten over time. Additionally, she found evidence that the work was originally intended for a small ensemble with only a few singers, rather than a large ensemble.

This study is significant not only for the performance practice of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater but also for the performance and study of other works from Pergolesi’s time.

One evening in April 2011, thanks to Steenbrink’s research, Holland Baroque Society performed Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater as it hadn’t sounded since the 18th century!

Special thanks to Tineke Steenbrink for sharing her research report with us.